Ksenya Samarskaya is a multi-disciplinary designer who, in addition to her breadth of creative and strategy work, is an incredible type designer. A consummate observer with whip-smart takes on the landscapes before us, her perspective provides a fresh and holistic approach to design and the greater world. She currently splits her time between Lisbon and New York. Interview by Elizabeth Carey Smith.

I was thinking before this interview, what do I want to understand about Ksenya? And I kind of don’t want to; I love the enigma that is you.

KS Hah. Well, the enigma is not intentional. Mostly not intentional. So I don’t think you’re in danger of making it disappear. I think you could keep asking questions, and the conversation can continue as a fully open and honest cycle, and it would still in some way be there.

It seems like you don’t entertain illusions—you have a level of groundedness and pragmatism. You’re not caught up in a fairy tale of America, or an illusion of inherent goodness. Is it because you’re Russian?

KS It’s always hard to retrofit a ’why?’ to a thing, because it’s always part fiction and part assumption and part poking around in the dark. I think there could be an aspect of Russianness. But in some ways, the reason Russians are that way is because they’ve lived through a lot. It’s lived experience; at a certain point you can’t afford to be blind to what’s around you.

Do you think that that is about trust? In the United States, we say we have this trust in our institutions, and perhaps in Russia and the Soviet Union, there hasn’t been the ability to have mainstream trust in institutions, because those institutions have failed people, many times.

KS To me, that kind of trust is naiveté. And the United States is a young country; I sometimes compare it to a teenager.

Temperamentally, for sure. I have a friend who’s from Romania, and she has a similar frankness to her. I was stressing about the election the other day, and she said, “why are you doing that?” And I said, “I guess because I think that if I worry about it, I can control it.” She just started laughing.

KS Until you’ve lived or been through a collapse or something like that, I think it’s really hard to conceptualize how you can both be inside of a collapsed system and still be living and enjoying your life. And it’s a situation where both are simultaneously true; that everything is falling or being destroyed, or has already fallen, and you’re still caring about what’s for dinner, and you’re still dancing, and you’re still laughing, and you’re still having to go through your day-to-day routine. So I think unless in some way you comprehend that—the construct of collapse—it might be hard to grasp what complete collapse actually means, or how it plays out.

You said that you feel a bit ‘both’ and ‘neither’, that you don’t feel that you have a home or nationality necessarily, that it’s kind of more nebulous? Do you think that that is also a product of that worldview, of being able to live despite all of what you’ve been born into, or what you’ve experienced?

KS I think that’s just a product of a fragmented history, of spending different formative years in different locations with different people.

So to that end, how much does your identity pull you toward certain kinds or groups of people? What do you question?

KS I think identity is inescapable. I think other people notice it more than you notice it, because to you, it’s just the way that life has always looked. So I think maybe it more comes down to how other people respond, or which groups accept you or which groups define the various meaningful, bi-directional contributions.

Does that inform how you educate others? Your students seem to come away with kind of a robust worldview insofar as it pertains to the work that you do in your class. What do you want students to understand most?

KS I want them to understand their own power.

I think that’s what it comes down to. I want them to understand that they are an active part of any situation they’re in; they are bringing something to it. And within the classroom, you start taking ownership and wielding it and learning how to use it. They are actively contributing to making the project—the group, their organization, the world—that they’re living in. So then, they can start thinking about what feels right. What do they want that to be? How do they want that to look, and after that, how they go about making that happen?

I find that’s important too. In creative fields, people often have self esteem issues, or are grappling constantly with ego, and criticism. There are obviously plenty of young people who have ideas about their own power. In Silicon Valley, for example, there are people who are building products that seem like noble pursuits, without enough understanding of repercussions. How do you think that we can best teach students the responsibility that comes with the power that they have?

KS: That’s all a part of knowing that agency is always with the flip side of responsibility. It’s being able to stand up to critique. And it’s being able to really look at a thing, turn it over, answer for it. To turn something around and keep inquiring about all the effects, not just going to the first question, not just the first answer. So my classrooms then become about the level of critique and the level of conversation. I encourage continuing to ask why, continuing to see how something can be improved, or how something can be honed in, even when you think you’ve exhausted all measures.

As people have been examining inequality in design structures, there’s a lot of criticism about how critique in school — if somebody cries or if somebody is hurt by a critique, that that’s a reflection of a power structure. While I’ve never made someone cry and don’t condone that, I also kind of mentally push back on that idea. When I was in school it was less about power in crits and more about me learning how to keep my ego in check when it came to my work. I had to learn that it wasn’t about me, it was about the effectiveness of my work or how much effort I’d put in. When I would occasionally cry after a harsh crit, it was about having to face the idea that I hadn’t done the work to address what I was communicating. Do you find that situations like that are reflective of an inequitable situation?

KS: I think it’s not very effective teaching. That it’s not how you get through to somebody, in terms of efficient communication. Generally, people understand and remember something if they came to the conclusion themselves. So my method of critique is asking a lot of questions and kind of leaving gaps for people to then make connections or jump through.

If you’re telling someone that they fucked up on something to the extent that they cry, there’re two things:

One, is you don’t know what they’re actually going for; you’re making assumptions. If you’re saying they got it wrong, especially when looking at creative work. Are you trying to get them to your finish line, or theirs? So I work towards getting the students to understand and clarify what their goal is, and from there, we can start navigating together toward understanding on whether they’ve reached it or not. Whether they can get closer.

The second part is motivation. If you’re just pointing out what’s wrong with a thing, you magnify the wrongness. And then, that can become almost too blinding to then find a road around or another path. So, trying to find what’s right, clearing off some elements of a foundation, and then building atop that, becomes a much more fruitful course of action.

Do you think that in order to be a good visual communicator, you need to also participate in other forms of communication, like writing and speaking?

KS: Not to be a good visual communicator, but in order to survive and make money as one. You’re gonna need to sell it, to explain, and negotiate; all the other parts in order to run a business, in order to work with a manager, in order to work with a client. You can make great creative on your own, but to participate in the system of getting it out there, you’re generally going to need to have other tools.

As a kid I liked to write a lot. That was part of my love of work. And that gradually became about letterforms. I always start with writing, because I don’t know why I’ve made something if I can’t rationalize it, specifically from a design point of view. Art is different, because you don’t have to justify it. A friend once said that, “the difference between art and design that art asks questions and design answers them.” Would you agree with that?

KS: Yes, ish. I don’t think it’s that clear cut. Art is capable of answering a lot of questions; you can be in the presence of art and all of a sudden feel very still. You can grasp at meaning. You can get clarity about interactions or social dynamics. And, well, take any piece of design out of its original context just a little bit and you might have all sorts of questions.

The sibling rivalry between art and design has often had somewhat of a bitter note to it. And, the division, it’s really a commercially driven one. I mean, design as an industry has existed for what, perhaps a century? Before people individually made things that were needed. There wasn’t a separate role of design. Design came out of industrialization, it came out of the factory, out of mass reproduction. It got caught up in colonialism. The history of art, and what art is, also meanders in and out of commerce in all these different ways. So currently they’re these weird siblings that steal things from each other back and forth, and play lil’ power games. I mean, take a trend like speculative design, it’s kind of fascinating. It’s art moving into the design space, and all of a sudden there’s this new way that it’s addressed or talked about or exchanged.

The way I’ve been thinking about it lately, as someone who has spent a lot of time in the amalgamated middle, is that there should be an umbrella term above it. Something like aesthetics, something that’s understanding how to create and understand visual literacy. Because when you develop that skill, you can pivot it to a lot of different ends, and I think you get better at participating in culture. Visual language is a code, just like written or spoken language, living in the objects around us and in the way we dress and our posture and the placard on the wall.

Your work is remarkable. I don’t even know how to qualify what that really is. That’s the feeling I get when I look at it, like, damn, it’s thorough, the concepts are big, and the craftsmanship blows my mind. I mostly think of you as a big ideas person, and I don’t hear you talk about craft a lot. What is the role of craft?

KS: I think you absolutely have to have both. Because they’re fused together; they loop in through each other. I’m trying to think of a good metaphor or way of explaining it.

Basically, our world doesn’t just exist in our heads. There’s no clear split between what’s in our mind and the physical world, however much Western thought likes to say that there is. To me, the details feed into the concept; and both are absolutely pivotal to make work that resonates. We absorb information with all our senses. Shoddy craftsmanship can speak directly to a hasty or weak idea, or a lack of confidence.

I’ve always had a deep belief in respecting the viewer. If I don’t invest the time and the effort up front in making the work, how can I expect them to give me their time looking at it or interacting with it?

Oh, here, the metaphor: Take a really memorable meal. It doesn’t become good just because someone had the idea of combining charred crab with linguine. It’s only good if the chef followed through with all those details to nail the execution.

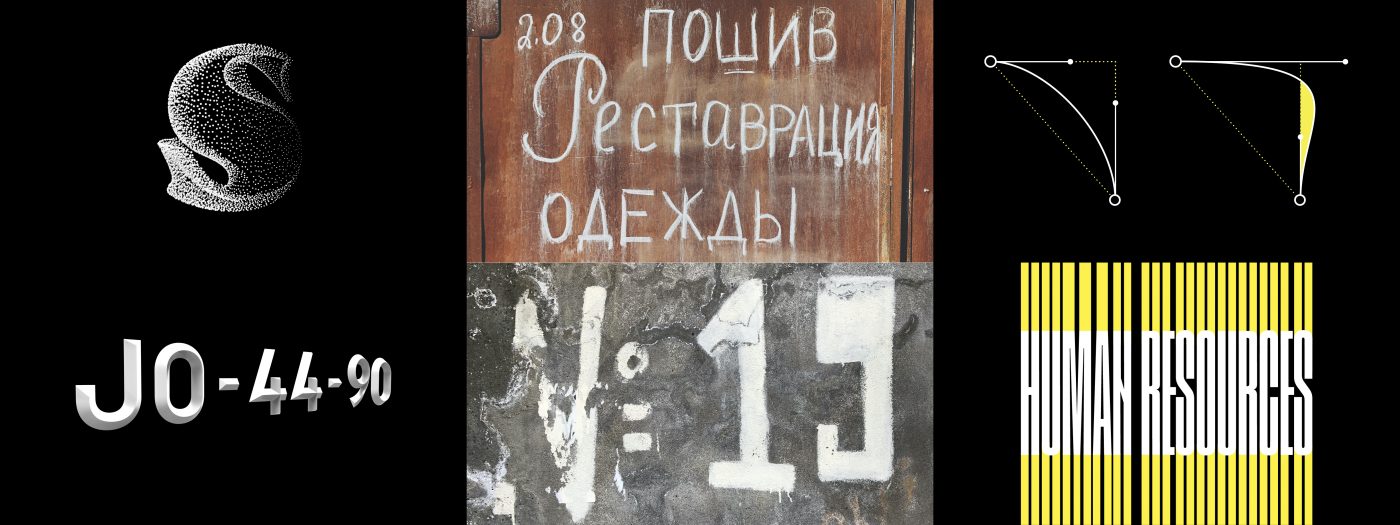

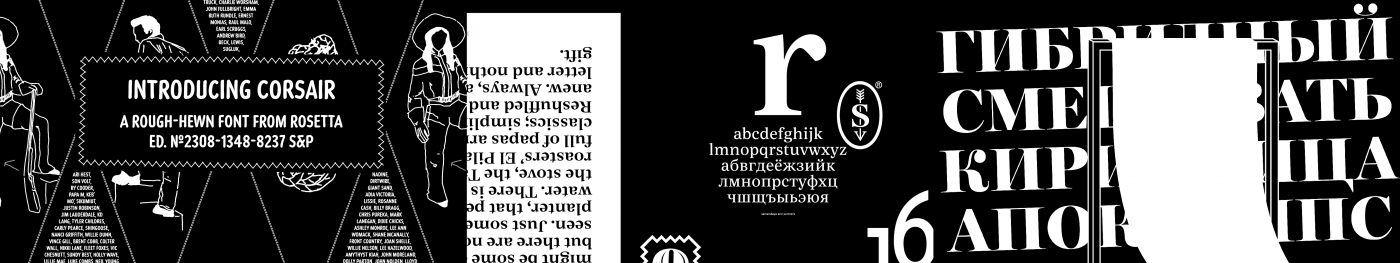

Can you talk a little bit about your craft when it comes to type design? Type is all about things like balance, rhythm, texture… could you draw a circle around your work?

KS: One of the first things, for people newly approaching type design, is being aware that there’re actually no hard and fast rules about anything. And I think that’s where people get scared, or they get stuck—so one of the first things I just really lay down is there’s no right answer. And once you realize there’s no one right answer, you’re free to start roaming around. You’re free to play and make it happen. At some point it really becomes about training your eye and your intuition—and working in an iterative way.

Do you define all of that as working within the construct of a system of your own making? Are you constantly thinking about making moves and shifting something around, but still within a construct? A simple way of thinking about type systems is, thick strokes go down and thin strokes go up, for example—

KS: This is where I think words might get in the way. Because if you can visually feel that thick strokes go up, and thin strokes go across, you might get something that resonates better than if you’re thinking, these are the rules and you do that all the way across. Because to get a really good texture, to get a really good pattern—for anything visual to feel natural and organic to us, you’re going to need places where you follow the rules and places where you break the rules.

Yeah. And then you’re relying kind of on that seedling intuition in order to make that…I don’t want to say right, because we’ve determined there’s not a right or wrong…

KS: Harmonious would be the word I think we’re going for. In text it’s aiming for even color, or the elements to coalesce and resonate, to sing in the same key.

How did you get to a point where you felt you could trust your own sense of harmony?

KS: Just practice.

I love that. That makes it sound so easy. Even though practice is hard.

KS: Practice and learning how to see. You spend time looking.

You’ve done a lot of work in different media. You seem very unafraid by other mediums, like that definition is irrelevant. I’m so afraid that I’m going to do something wrong—like when I look at old letterform work and cringe at how I didn’t know or see it properly, and I am afraid of being naïve in other mediums.

KS: Well, that’s what I started with, that’s my education. My education wasn’t in just one specific medium: it was conceptual art, theory, installation, new technologies. And so it was about how you ask questions, how you look at things, how you interrogate a subject, how broad and deep to research to find the spark, or the element of intrigue. And then, it was do whatever you have to do to make your vision happen. I had a wonderful teacher who was very unapologetic about that. There was a hard line: you either bring it, or you don’t. And if you hit obstacles, it’s on you to figure out ways around them, to think of some other way that you could still meet your objective out of what’s at hand, all factors considered and everything on the table. And to me, that’s a much more beautiful way of teaching. The world, in all facets, not least of design work, is constantly evolving. It’s impossible to get in school, once and for all, all the technical skills or understandings needed down the road. So then it becomes, how do you develop the habit to continually keep learning what you need to learn to achieve your goal? And how do you accept the world as is, with the obstacles it presents?