Elaine Lopez is a multidisciplinary designer and artist whose prolific explorations are helping to shape new narratives in graphic design. Lopez’ work—involving interaction, systems, and printing—is informed by her Cuban-American roots. She currently lives and works in Philadelphia.

Elizabeth Carey Smith: I thought we could start with the easy questions, haha. What isn’t challenging you right now?

Elaine Lopez: Yeah, that’s a hard one. No, I really enjoy teaching. When we’re in the Zoom and people are sharing their work, and it’s working right—I find that to be so energizing. I always find teaching to be energizing. I think the prep—like, what are we going to talk about today—all of that is very challenging, but when in that moment, it feels like everything is right in the world. We’re in a room with people, people are making amazing stuff, we’re giving feedback, it’s great. Or just hearing how people are grasping concepts, or realizing things or even just sharing what they’re going through right now. I just feel really fortunate that I get paid to do it.

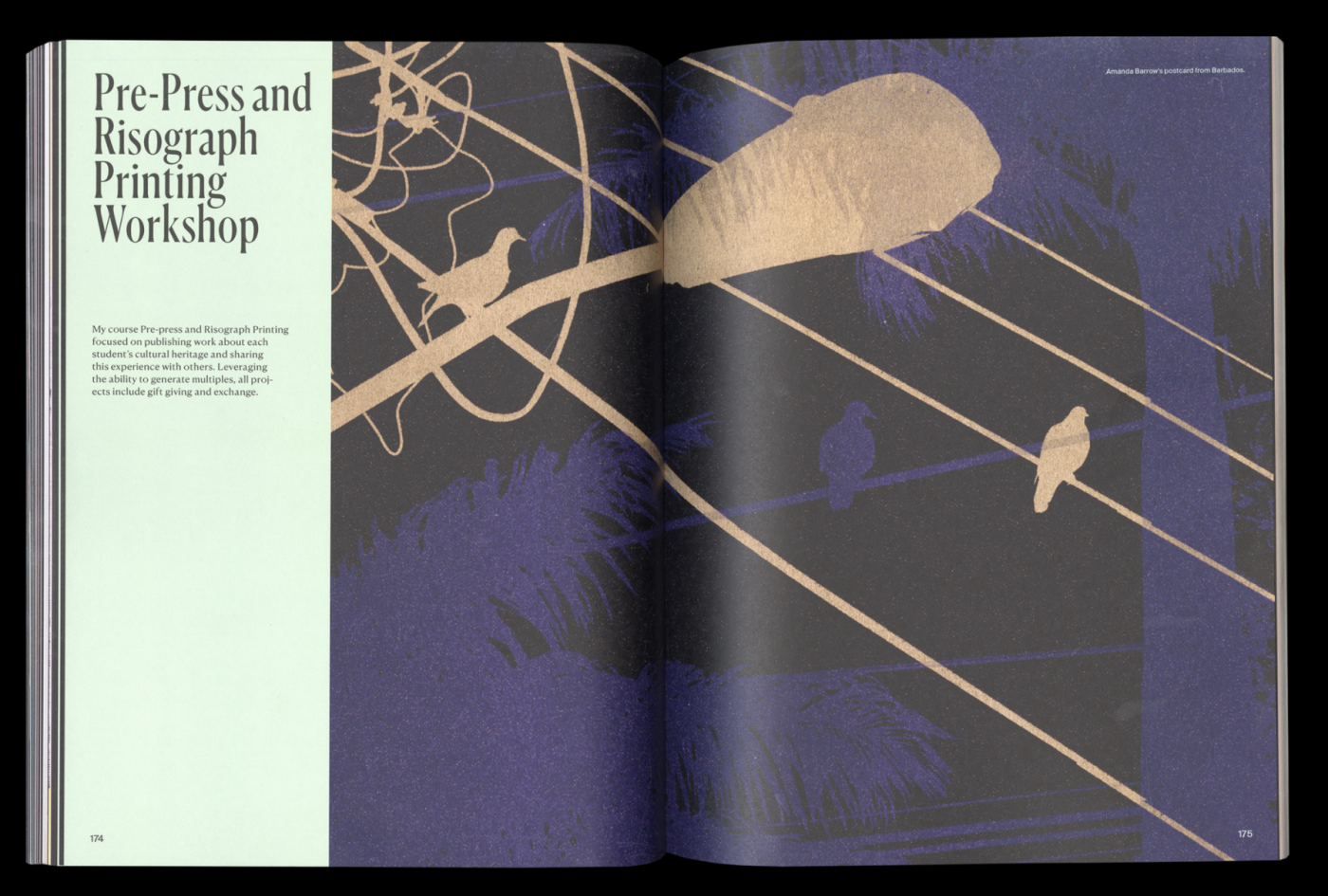

And it’s such a different way of being a designer than working and, you know, cranking out a project. And yet, I feel like they are two sides of the same coin still—you’re designing a lecture, you’re designing the way that other people are going to experience something. So that and then Riso printing whenever I get a chance to do so is usually really nice and fun, and just like, physical and beautiful and rewarding. The balance of those two things, I think, are keeping me sane, because everything else is impossible.

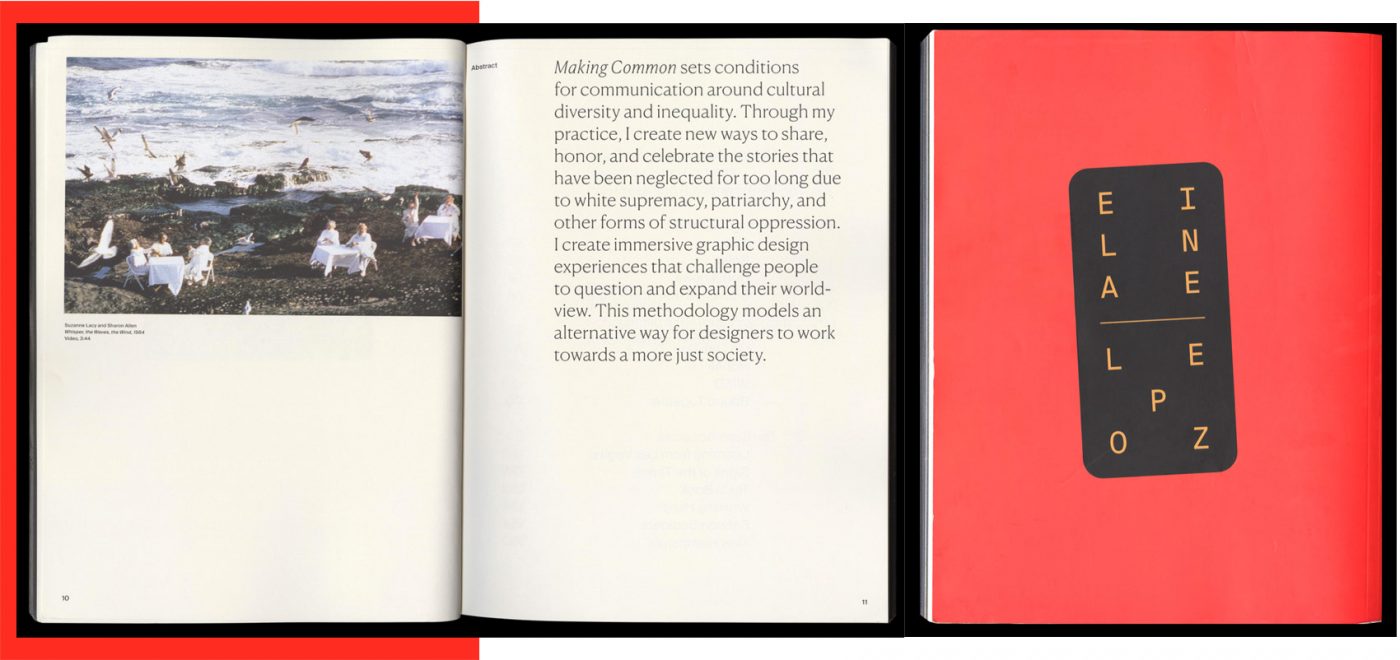

Making Common, Lopez’ 2019 RISD MFA Thesis

ECS: I’m glad you touched on both of those things, teaching and printing. Were you creative as a kid?

EL: Yeah, totally drawing all the time. Even from a really early age—my grandmother kept this drawing of an apple from like, preschool or something. And the teacher said, Oh, this is really good or whatever. I was always in my room drawing, and watching MTV. I was not outdoors [laughs] I was just indoors, making things.

ECS: Your work now is really involved with systems. Was it kind of a happy accident that graphic design is all about them, and that you ended up studying graphic design, coming from a traditional art perspective?

EL: Yeah, that’s a really good question. I went to the University of Florida for undergrad and I remember when the guidance counselor asked me what I wanted to do. I was like, ‘I like history and I like art.’ She told me to take this art course, which was intentionally a weed-out course to get rid of people who weren’t really serious about art, and it was all about conceptual art—it was a very intense class. But at the end of that, they said, ‘you should consider graphic design.’ And I really didn’t know what graphic design was, I hadn’t been exposed to it in high school, and in fact, my art teacher in high school said that graphic design is really hard, you shouldn’t do that. So I thought, oh, I guess it’s hard, and I don’t even know what that means. This was the early 2000s when I was in school, so I don’t think design was being talked about in a way that it is—we knew less about design.

But I remember taking my first typography class and being like, Oh, this is really hard, actually. It didn’t come to me as easily as illustration did or my photo classes—I liked all of that. But with design, I specifically remember having to take a long walk after class one day and thinking, What am I doing? Why is it so hard? I couldn’t figure it out, and I was really intimidated by more senior people in the class who seemed to get it and were able to produce beautiful design. And I was like, why am I struggling at this? So I think it was actually that challenge that drew me to it a little bit. I was attracted to the functionality of it. With design, you could actually impact people and communicate things and it requires a little bit more thought.

So I think that’s why I ended up going down that path, and then financially too, I thought I could probably get a job as a designer more easily than being a painter. And as a first generation person, where nobody in my family had been to college…before I went, I really had no idea what I was doing, and my family was pretty hands-off. They were like, okay, yeah, do whatever you want to do. And so, you know, I was thinking practically a little bit as well, it felt like I could get more of a realistic job. And I really enjoyed it. Studying design in undergrad, I was the president of the graphic design club my senior year, of course, because I was a huge nerd. I was always just really involved with school and activity and school governance. I’m just that kind of person, I got to be involved.

ECS: Education has become (I think) wrongfully synonymous with job preparation. You advocate really strongly for education as developing ways of thinking, that can, of course, inform how we work professionally. I’m really aware that many of my students, many of whom are Black, or brown, first generation, undocumented—are already taking a risk in some ways studying art, like, flipping their family’s perspective because there’s often a real pressure on them to commoditize their education somehow. Sometimes I worry that while I know that I’m helping them cultivate these ways of thinking, I also want to make sure that they can go get a job. What do you see is that that gap between someone’s education and (especially their first) design job?

EL: I think it’s so prevalent in these communities, specifically, because there is this pressure—this is so deep to me, because it even goes into challenging white supremacy and the decolonization of design. I really think that that’s what this is about: welcoming different people into this field, into a space and teaching them that their experiences are valid. And the places where they came from are just as valid as these other experiences or things we read about, or study or do…sort of opening up design, what you can do with design, but also how we teach design. Ultimately, I believe design education is about confidence. It’s instilling students with agency and the confidence that your decisions are valid, and that you should be able to use design to express who you are. Take these tools and really add to the canon of design by sharing your personal experiences. Versus like, make this pretty logo, you know, whatever, go get a job—which I also recognize is super important.

So it’s this fine balance of both teaching people skills and how to use the programs and what proper typography looks like. But also, having them understand that now that you know those skills, use them to talk about something that you’re interested in—whether that’s your culture or your experience, or even, you know, maybe you love surfing or whatever—but use design, to express yourself and your identity, and make something and you really believe in.

In a job interview setting, those are the projects that are most interesting, because they not only showcase the person’s ability, but in an interview, you want to know who that person is and whether you want to work with them. If they are sharing a piece about their culture and heritage, and it’s beautiful, and you learn something about that person, I actually think it’s more effective than here’s a logo I did for Staples, or whatever, which, like, cool, how many of those do you see in an interview? It doesn’t say anything about the person who made it. So that’s how I believe you walk that balance.

But as a first generation college student and person in this industry, it’s hard because you feel like you need to be whiter, or you need to hide those parts of yourself. That stuff’s not encouraged, you’re weird, because nobody knows that, or nobody speaks the language you speak, or comes from where you come from. What I think happens mostly, and what happened to me was that I wanted to be white—I wanted to get rid of all the parts of my heritage because I wanted to fit in—to fit into design, when you see Paul Rand and Paula Scher— these types of people that don’t really look like you, then you’re gonna fight to be more like them.

Over the summer, when I was speaking at [the July 2020 conference,] “Where Are the Black Designers?”—if you just Google, “famous graphic designers”, that’s an experiment you can do right now, and you’ll see it’s all white people, primarily, all certain types of white people. And it’s so discouraging.

I think, for a lot of people, myself included, I’m still…I don’t know, the fact that we’ve been doing this interview, I’m like, Oh, that’s weird. You want to talk to me, but who am I? I’m not Ellen Lupton, or whatever. But I think through grad school and through studying this stuff, that I realized, oh, no, actually my perspective has value. I need to speak more loudly about it so that other people can see themselves in this industry. That’s where I’m coming from.

I want other people to feel that way too, to say, I am from x country, and I’m a designer. And this is how I see design. This is how I use these tools and the skills that I’ve learned to communicate this new experience. I think that’s how we innovate this field, how we start companies that are not just about the same shit we’ve been doing now. We need to bring in more, different kinds of people, so that design can grow and be more interesting than I think it is sometimes.

ECS: Yeah. I was glad to read that one of your first jobs had you doing a lot of PowerPoint, and that it became a lucrative skill, because I don’t think we hear enough about people’s trajectories that don’t begin with a fancy job, or the most satisfying creative work. Not enough people see these stories and how difficult it can be—you can go from being a good, curious design student, to a junior designer who has a portfolio of things that don’t really reflect how they think or what they can make. Can you talk about what it was like in the transition between those jobs, building your portfolio, and how you applied to better and better jobs?

EL: Yeah, I’m working on a PowerPoint right now. I’m so glad you brought that up. Because I think the majority of design jobs are that, you know what I mean? And we idolize these other types of jobs that are like, Oh, sure. You had Nike as a client. Of course, you made something awesome, right? But I’m working with posters, and when was the last time anyone paid you to do a poster? That’s so rare, because where do posters even live when everything’s online? It’s a web ad, like, let’s be honest. So I hate that this industry doesn’t have that honesty about it. I think I really struggle with that and I try to be really transparent with my students about that—your jobs are not usually going to be this glamorous. And that’s okay, but let’s treat this industry the way it is. Yeah, it can be mundane, but we’re not like, laying down railroads or whatever. You know what I mean, it’s not the worst thing we could be doing with our lives, but also this idealization of certain clients and certain types of projects and budgets and things, I think, contributes to how exclusionary this field can be sometimes.

If I think about my own trajectory, the first design job I got was whatever I could get; I was in Miami, and it was a boutique studio that did ads for car dealerships, and they also had Ritz Carlton as a client. It was just random. I was just happy to have a design job at all, you know, as a student graduating—you just take what you can get. And then I moved to Chicago after that, and I kind of had to start over. I didn’t know anyone. I went through Creative Circle, and they got me a job at this pharmaceutical marketing company. It was fine, whatever, you know, but it was a place no one had ever heard of. But I actually met some really wonderful people there. And I think I really learned a lot and grew as a designer. We were designing apps when no one knew how to make an app yet. So we’re kind of making it up as we went along. And that was pretty cool to learn that. But I had this weird feeling, like, nobody knows this company. I had this chip on my shoulder.

But that’s sort of what pushed my trajectory in this industry. It was like, Oh, I need to work at somewhere cool, so that my friends think I’m a good designer or whatever, right? After that, I met someone through my social network who worked at Leo Burnett, and I was like, everybody knows what that is. That’s my dream job. I’m gonna go work there. And I did, but I was designing shelf talkers for Walgreens for big clients like Olay. Again, we don’t talk about this in school, like nobody thinks about designing stuff for Walgreens, and yet, it pays the bills, and it’s a really important part of design work. Those companies have money, and that’s what design looks like in certain industries. I did that for awhile and then realized it was kind of boring, that I was designing trash, because this stuff literally goes into the trash after the product is sold, and I felt kind of like I was manipulating people into buying a specific detergent that they may or may not need. And this felt really unfulfilling.

So again, through my social network, I met someone who worked at gravitytank, which was a human-centered design place. I got that job eventually just by being really annoying via email. I really wanted to work at that place, and I thought, I’m going to reach out to y’all super often to see when you have an opening. Please take a chance on me, because my background is advertising, it’s not human-centered design, but I believe that this knowledge can transfer. And that knowledge did transfer! But then I also learned how to do all this other stuff, like research and strategy. I finally felt valued for my thinking as a designer versus just my abilities to manipulate Photoshop or make something aesthetically beautiful. That was really empowering.

After that I worked at Greater Good Studio, which was taking that methodology, but for social impact—how do we help nonprofits and schools? How do we better the world and not just sell more products? But also, we’re speaking for communities where I don’t necessarily feel comfortable—I was worried about the ethics of human-centered design for social impact, which is a hot topic now. But it kind of rubbed me the wrong way, a little bit. And then Trump got elected. And I was like, I need a break. I’m gonna go to grad school, and think about this stuff.

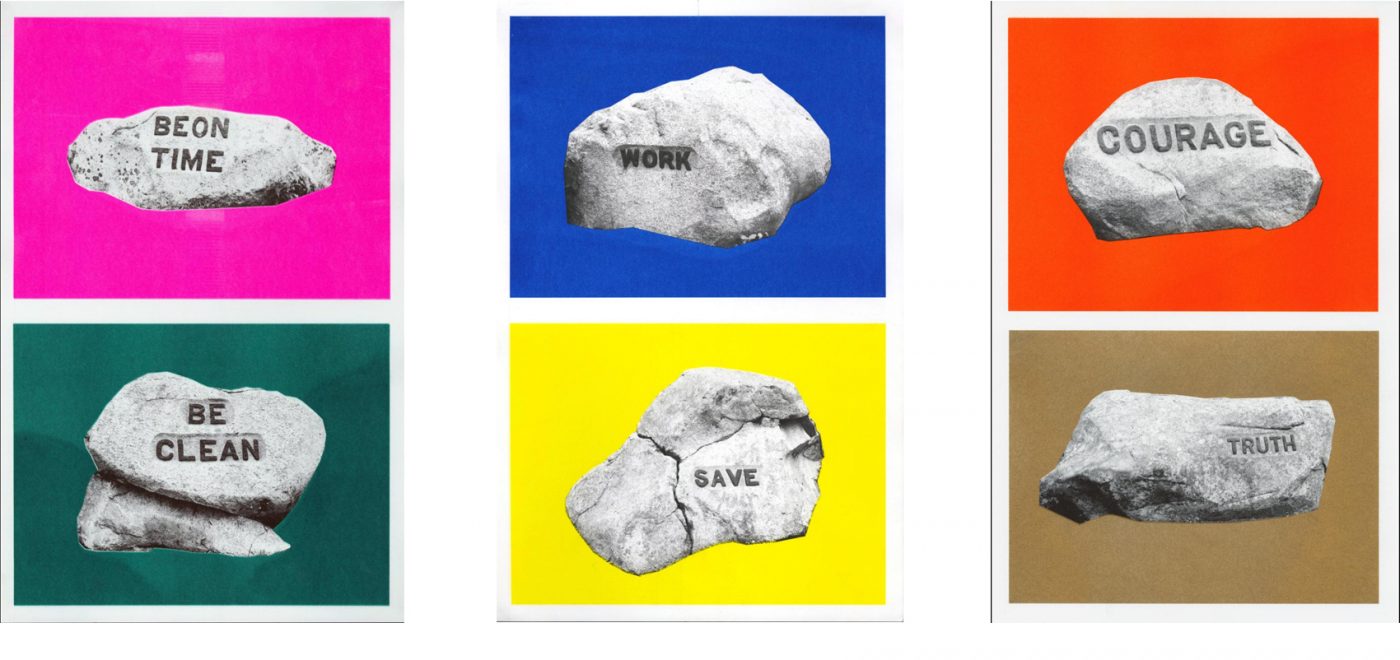

Babson Boulders, by Elaine Lopez

It was there where I was actually able to think and read things and realize, I’m not alone in this, and I could observe the flaws within design education, firsthand. I was like one of two people of color in RISD’s GD MFA program of 37 people. I was like, Are you kidding me? This is 2019. You hear people talking about diversity, and yet you go to these programs and I was, like, Where is everybody? You’re gonna tell me there’s not a single Black person here? What the fuck is going on? And realizing that people are not entering these spaces, and that the problem of lack of diversity starts with education. That is maybe even the worst thing, that’s where it starts. And that’s what I’m trying to focus on, to sort of challenge that, and ask how we bring more people into these schools and programs and introduce people to design and make design for different kinds of people.

ECS: Your work moved into a more critical space. Can you talk about advocating for design as a tool for reconciling what’s inherently problematic about design in the commercial world?

EL: This is maybe my biggest question now: what does my practice look like? I’m struggling with it, to be honest … I’m still freelancing, and doing PowerPoints and dumb stuff to pay the bills, but also thinking about grants and a project I really want to do, and how I get that funded. I’m not thinking about a deliverable or commercial stuff, but how design can be about experiences and about helping people connect with each other. How do I turn that into an offering, which can become a way to practice design? I struggle with it. I think it’s something we all really need to think about as an industry…Where are we going? What are we doing with this with these skills, and these abilities that I still, frankly, believe are super powerful and really important to society?

ECS: Your parents fled from an oppressive communist regime—how did their politics and their lived experiences inform yours and how you think about the world you grew up in?

I grew up in a really Republican place—Miami Cubans are super Republican, because growing up you learn that Democrats are communists. But my family didn’t even talk about politics—my parents themselves weren’t super political. My grandfather, however, was a political prisoner and was jailed for six years, then fled. He would listen to this right-wing Cuban station, which still exists actually and is partially funded by the CIA to basically radicalize this population. Not even radicalize, because Cubans hate Castro, right? Communism was not great—it really took everything that people had: imagine someone coming right now and taking your home, taking your business, taking everything from you.

Then you have to go somewhere else, where you don’t speak the language…you’re gonna be mad about that. That is some deep trauma, being jailed, people being killed, it’s a very traumatic situation. And so, of course, the Cuban community feels that way.

I took a class at Brown on the history of the Cuban Revolution, and I would literally weep during class because I didn’t know this stuff. I was 33 years old, learning about my family’s history for the first time.

I believe in education for that reason, I believe people should have the opportunity to like research beyond what your parents tell you. It’s sort of what’s influenced how I see the world now. That’s why I feel like as designers, we have the ability to educate people. Talking about Cuba feels like a responsibility and something I would love to do.

Imagine if everyone did that, from all the different places that they were from, and made these really beautiful design books and objects and films and websites about all these different places, so we could learn this stuff from the person who experienced it. I think that’s awesome. I can’t think of a better use for design.