Elizabeth Carey Smith: How has being a parent changed your perspective, from a work standpoint, now that working and parenting are kind of in the same space for you?

Douglas Davis: I think, in some ways, it has forced me to slow down. And I think in other ways, it's also forced me to really think about what priorities are. Because it's not like you don't have a two year old who needs your attention and your love and who's looking for your affirmation just because you have a work call or a deadline. When work moves in with you, you've got to just figure it out.

We're all here. Yeah being able to kind of share my day with my daughter and have to stop and figure out a long division problem is not a bad thing. And also, no one's offended by it. I don't know why I thought that, like, people would be upset if a kid comes into the screen.

And to be fair, you know, nobody invited everybody into their homes. And yet, here we are, and so work actually is infringing on the kids’ territory. Work is infringing on their time. I think it's really important for us to realize that. I'm just glad that part of life potentially is at least just being rethought. Because there's no other way to do it, until it's safe to go outside.

What were you like, as a kid? What were you into?

Um, gosh, as a kid, I lit fireworks in the house.

Did you grow up in New York?

I grew up in South Carolina.

A little more room for fireworks.

Maybe a lot more room but not in the house. I also fell out of a moving car, I guess this was before seat belts or car seats. I just remember the turn happening and, you know, I fell out into the intersection. Thank goodness, nothing happened. But I was always in something. You know, took a little swig of Clorox.

You're an E.R. kid.

Yeah, pretty much.

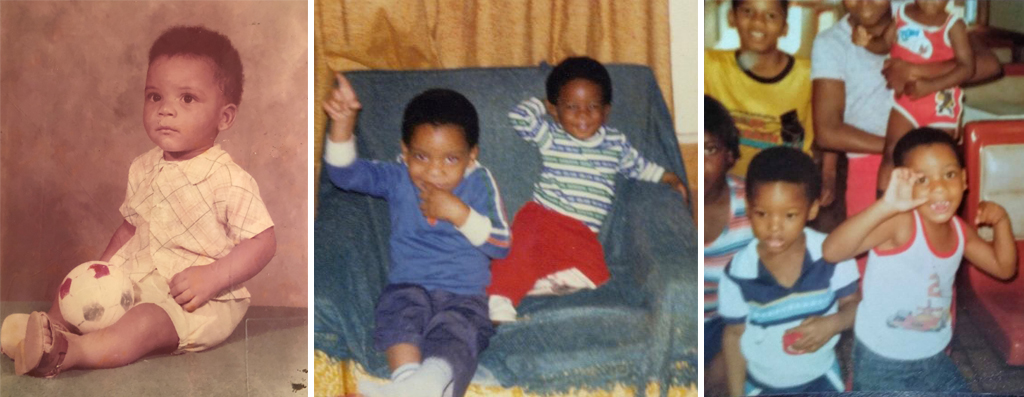

Early Years in South Carolina

Would you expand that to say that, maybe you were a curious person from the jump?

Oh, very, very curious. And thank goodness there's aunts and uncles and cousins and grandparents and...you need a team! To make sure he’s okay. Where is he? What's in his mouth?

Were you always visual?

Yeah, definitely. I remember. So the state fair back home is this big thing. And everybody's like, excited to go. My older cousins took me one year. You know how you throw the darts at the balloon and you win something? So they did that and they won a Garfield mirror. And I went home, sat on the floor and I drew it. I showed my mom and she was like, You didn't trace that, did you? And I was like, nope! It was great because that sort of showed my mom how to channel this energy and curiosity.

Back in the day, they had these mail-order art instruction schools. You could draw the pirate or you could draw the turtle. I don't know where my mom got the money to do that. Because it wasn’t like we had all this money, but to have the encouragement of being able to draw something and send it off somewhere — Chicago! And have people give you a critique in writing and send it back to you...someone took the time to actually comment. I wrote Jim Davis one time, and he wrote me back, and it was truly amazing.

So I grew up sort of wanting to be a cartoonist, and just going through the normal things that kids, you know, down south, or I guess maybe everywhere, drew. You know—you start with shoes, and so you're designing shoes and typography on the Nike, or you're, you know, drawing Marvel characters, and stuff like that.

So the progression through just being able to look at something and reproduce it without tracing, the attention to detail to proportion and line shape, form, space, color variant, texture, those sorts of things. You don’t do that for a grade, this is what you love to do.

And it's good, because I was bored and all over the place, and I took that to school, so I was going to the principal's office or doing something crazy, so now I got in school suspension, and it was one of those things where sitting there, I could draw all day. It was good to be able to channel as I got older, the ability to focus and channel all that energy into the art program in my really small little town. It really changed my behavior, because there was somewhere to put it all.

When you got letters back from the correspondence school, and they were validating you as a kid and a person, that did help you kind of shape your identity for yourself?

The good thing about being from a southern Black town is that there was always this understanding that there was an education after you got home from school. Because of the history of separate but equal, needing to be a self-sufficient community. So what was great is that, you know, you had that village, and it really was a village. A lot of what we were taught at night, or taught on Sundays, was not just through my family, it was through the community. So I always knew who I was. I'm thankful that I was always seen and I was always invested in that way.

I think I didn't realize that everybody didn't grow up like that. So it was a shock when I left the South. I was like, Oh my goodness, there are people who don't like being around their families or they have families that don't necessarily have the same composition and unity. That was new. I didn't realize that at all.

But it was great to be seen. I would say, I want to be an artist, and everybody was like, you know, he's an artist. And that was a good thing, because when I was 24, after I already had a Master's already, I learned that there was a lot that my mom probably protected me from. I never really heard that you're going to be broke if you're going to be an artist or going to starve or all that negativity. And I'm thankful because I wasn't privy to any of that. I never heard any of that. I was always encouraged. I was always positive in that way.

Davis attributes much of his strength and ethic to his stable and loving family and community in South Carolina

That is a unique experience. Did you go from South Carolina to New York?

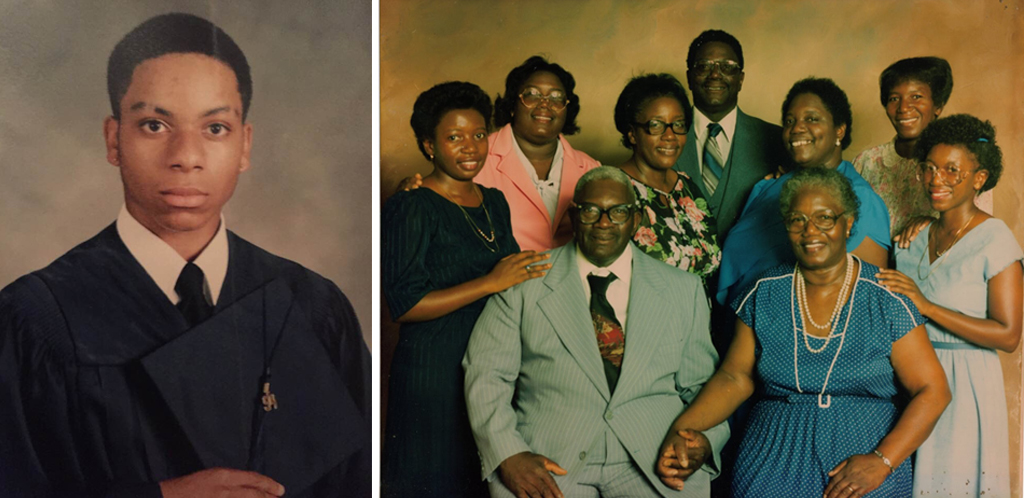

No, I went to Hampton University, Virginia. I never had a conversation with the guidance counselor about college. But I did say to myself, probably around the summer of 11th grade, if I don't go to college, I want to make sure it’s because I chose not to go. I voluntarily took summer school classes, the extra math and extra foreign language requirements… I took the SAT like three times just to make sure that if I did want to go, I’d have options. That's what was most important for me at that point.

Fast forward, I've already graduated high school, and I'm volunteering at the Urban League. I stumbled onto a conversation where the vice president of admissions at Hampton was talking to five other people … I come in on the tail end of a conversation where he says, Well, if you have the college requirements, you should apply.

I went home that night and said, Hey, ma, you know, I'm going to go to Virginia. And so I applied and I got in, thinking that I'm going to go study, fashion merchandising. And so my mom packed up my stuff into the car, and we drove six hours north.

While I'm unpacking into my room, she walks around campus one time to see what she's paying for, and waves at me on the way out, and I go do all my business, register for my classes. And when I get to registration, they tell me that fashion merchandising is phased out. So I say, Well, you know, my fashion interest is only symptom of the art stuff that I like. So let me choose this graphic design thing, because I've never done that. But I've done all this other art so I'll learn something new.

What's great about that experience is that I could practice the things that I had already been doing—the wheel or printmaking, drawing, ceramic sculpture, stuff like that. But I could learn graphic design and I learned about photography for the first time, while practicing these other things. And so it was great to be able to go from South Carolina to Virginia, and to really learn in a focused, much smaller place than where I actually came from. It was really international.

One of the biggest lessons I learned in Hampton was just how diverse Black people are amongst ourselves—different accents and socioeconomic statuses, and I learned that we're much more than what you would see on TV at that time, like Jerry Springer.

And that was a really wonderful part of my education at an HBCU. But I think the biggest thing that I learned there was to continue what my grandfather and my community at home taught me: if you're going to do something, do it right. At home, it was cutting the grass, or it was sweeping the floor, doing your chores. It was great to be able to go to a really prestigious HBCU and take that work ethic from the south. My talent was what I was investing in.

Design Students at Hampton University

That’s so wise of you to even understand at that age what making options for yourself entails.

You know, I think I have to acknowledge, and I do this in my book, I mentioned my grandparents, and I tell them that “my students don't know that they're your students.” Coming from sharecroppers—the sharecroppers’ grandson. And to know that these people who didn't finish the fifth or sixth grade, still teach me from the grave, still teach me more than PhDs and people who are smart by these other, sort of learned metrics—to know that this sort of lived experience was what I was immersed in back home coming up.

You know, every little kid is like, Oh, that's my car. That's my house. But to have my grandma from the beginning, correct us and say, “Don't say that, that's your car. Say you want one like that." That small little correction, handled the envy, the thinking that, to get mine, I got to step over you, because there's not enough and so I'm gonna take yours to get mine. I'm thankful that I never experienced those things. Because the way life was presented to me was through the lens of these old people and this community of people who knew that they needed to invest in their own children, their own businesses, their own community. It's just really great to know that those lessons—always have time for old people, to be humble, that manners will take you farther than a lot of things...those things that my grandma would always say. Those seeds, that investment, all of that was there, and I was able to watch it, because that was normal life.

And so to leave that context, and take all those lessons, I'm thankful that there's some part of me that will always be a grandson who wants to be with Grandma, or go fishing with Granddaddy. It has really made a mark on me, from fashion, and how I like to mix things, to just how I really do love people and being around people. It energizes me, it's a really big part of my core.

Yeah, that's beautiful.

Thank you.

Were you always interested in fashion? And what was the bridge after Hampton? Where'd you go from there?

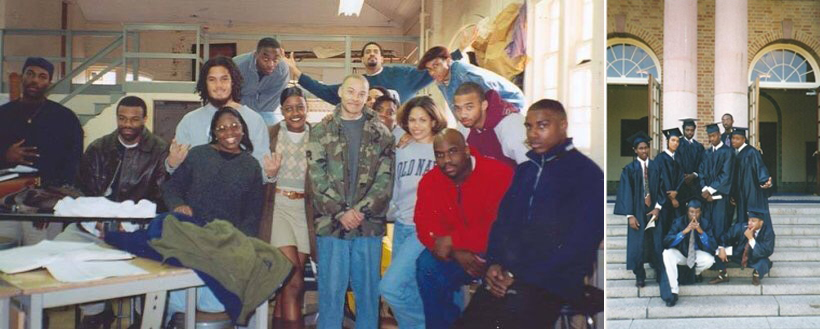

While at Hampton, I had a Disney internship. And I was a tour guide around Washington, DC, learning all the monuments and memorials, and I did a microgravity Hampton University internship just to design the publications for K through 12 kids about microgravity and science, and was at the Smithsonian several times when I realized that I needed more. I took two elective advertising courses while at Hampton electives, and the professor suggested that I enroll in Pratt Institute. So I filled out one application to undergraduate, and I got in, I filled out one application to graduate school, and I got in. I thought I needed a little bit more polish anyway, even though I was graduating with a resume of work, I didn't feel like I had everything that I needed. So I went from Virginia to getting a Master's—I went straight through. I was 21.

When I was moving to go to graduate school at Pratt in New York, I was like, Oh, my gosh, I'm moving to New York. You know, that fear mixed with excitement? Can I compete on, you know, the biggest stage? Am I good enough to go and do that? And, you know, the biggest challenge is being broke and being poor. I had somehow gotten through undergraduate and basically, my master's before I realized, wait a minute, I think we were poor, like, I'm not sure, but I think so. And what was great about that is that I had all the support that I needed, and then some. But I think a lot of this goes back to me being an artist and me being like having so much energy and needing to put it somewhere. So whether it's fashion or something else, it was about standing out. It's about being able to say something about yourself and the way you present yourself, and I felt like I brought that to my work as well.

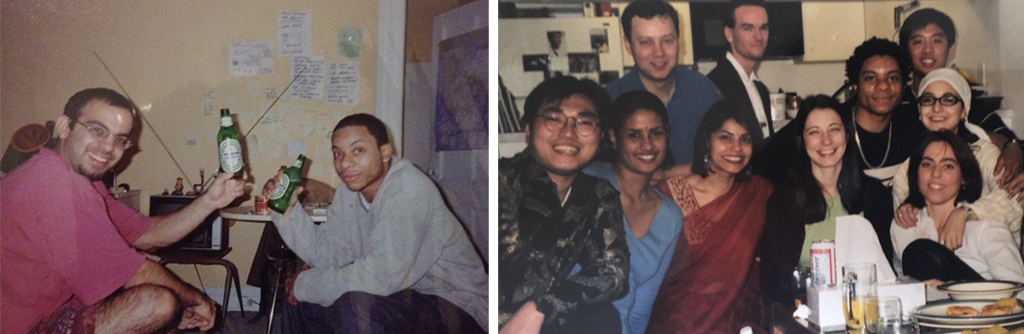

Davis and friends during his first years in New York City

Over time, I realized that teaching is an outlet, and I needed some sort of metric to make sure that I'm doing it on a really high level. And I like client service as an outlet. So those were really my three pillars, I've always had to have some sort of mix of those three things to stay in balance, being able to teach undergraduates the craft of what we do, the aesthetics, the conceptual part of things, being able to have an elevated conversation with graduate students on the strategic side of things, really going deep.

I don't have anything to offer you in the classroom if I can't actually serve a client. So my own metric is, as long as I'm valuable in the boardroom, then I have something to say in the classroom. Having and protecting that professional viability is something that’s important to me, personally. Because we've all had professors or teachers where you could tell their heart's not in it, it's a paycheck. They actually hate this job, hate kids, they hate teaching, they hate life, probably. I never wanted to be that person, where people could say, you're not here because you love it and want to be here, you're here because there's nowhere else for you to be.

I think students, especially right now, who are lucky enough to be in school, or about to make that transition to work (which is always hard in normal times) they need to know, what do I do with what I have? How do I use this to put food in my mouth, to make sure that the light comes on when I click it, I can sleep inside, you know: What do I do with this?

And what do you tell them?

I focus them away from grades and towards learning. If you don't correct the thinking that all you should want is a good grade, they're focused on the letter. Nobody's going to see them—which is why I put my grades in my book, because I was making the point that if I didn't do that nobody would ever see my grades and they wouldn't care. It doesn't matter.

It's almost like assessing what you do at work by your check stub. It's these stupid letters. Maybe we need to rethink these measures of potential. You can't allow outward measures to determine what you think of yourself. If you believe in you, then let's get it. But you can look to the right and see what it looks like to see someone's absolute best. And because that has nothing to do with you, other than it should inspire you, you can be happy for them genuinely. And then you can ask yourself, what is my best? What does my best look like?

Because even though we're running, you're competing with yourself, to be better than you were last time. How are you going to take it higher? What do you need to do to be better than you were? And I think that that, that always focuses students back on what they can control, versus all the other things that make people afraid and insecure.

I think a lot of the stories that I can tell include a bunch of failures, include a bunch of bad decisions. And since I started so young, it's been 22 years, so I can say like, yo, you know what, I sat in your seat before, I've worn your shoes. I'm not gonna ask you to do something that I haven't done, or that I'm not currently doing with a client right now, never gonna waste your time. But I'm going to demand excellence, I'm gonna give you everything that I have, you will be able to call me on this phone no matter where I'm at in the world. And until I'm cold and dead in the grave, I will answer you. When I asked for everything that I invest in you back, you better give it back to me every single time. And what's great is that when you can believe in students before they believe in themselves. Over time they start to believe your confidence in them. And so it's just really great. When you can see the visible frustration on their faces whenever they say, “tell me what to do”. And my answer is always, you pay for the questions, not the answers. That's the undergraduate version. The Graduate version is, we just jumped out of a plane and I'm the only one with a parachute and I will not lift a finger before you to hit the ground, unless you do something,

I teach how to work through ambiguity. I'm never going to give you the answer. But that's because I'm going to teach you how to survive. And what I appreciate about that is that my undergraduate students, some of whom live in the projects, and you can help them to change their lives and the lives of everybody who comes after them. By just helping them to use what they have. Yeah, listen to my grandma, use what you have.

Davis, teaching

What are some immediate things that we should expect from industry and from our learning institutions, with regards to disparities of representation?

We're living through a time where our institutions are failing us—whether we're talking about, you know, priests molesting kids, governments not actually like helping people, and just being dysfunctional, colleges and universities taking people's money and not actually helping them to get jobs … no matter why we go to a job, or a brand or university or whatever, we're all sort of showing up with various forms of that exact same question, which is, do I belong? And based on the collective experiences with that institution, at different points, over a certain amount of time? The answer becomes clear in the way you're treating me. And if I reason out, that I don't belong, because of what you're telling me, every time we interact, over time, I'm going to go find another place where they're having the conversation that I need, or I'm gonna find another church group, or I'm a finding wherever is actually speaking to my needs.

And I think companies and brands and institutions and countries have to ask themselves the opposite side of that question, which is, are we relevant? And the answer has to be based on how many people there who can say, I do belong.

They also have to look at the groups of people who've decided that they don't belong, and understand, what was it that we didn't do? or did we do that? If they care, they can go get those people and decide to ask, why weren't we relevant to this group? Why don't LGBTQ people feel comfortable here? Why do Black people feel like they're not able to be themselves and wear their hair however they want? And I think that's the context that we got to start looking at things within. If you can do that, then we can start to come to some conclusions.

We need to communicate to underwriters and to groups who probably have a harder time becoming stable in certain ways that white people don’t have to, because of slavery and all the things that were expected and taken and exploited. Acknowledging that that was the case, knowing that stability is probably even more important to certain people.

And identifying the people who are tasked with planting the seeds of possibility in a young person—counselors, moms, the people who are older, the ones who say you could be whatever you want to be—which is what I was told—if those people don't know what engineering is, there's no way that they're going to suggest to you that you become an engineer. Even when we drive across a bridge, we touch the elevator button—in that context, engineering is invisible so it’s not even an option, right? So I think about that, as it pertains to creativity.

I think it's important to recognize that we have to start putting our finger on what design is, because there are more design decisions than there are visually literate people to make them. And therefore design is only visible when it fails. Because most people in underrepresented groups don't know what it is, even though they depend on it every day, from the cradle to the grave. And so I think being able to explain that to people, and point out all of the different things that are designed that they are familiar with, and use and depend on. The packaging in your refrigerator, or going into your closet and picking out brands...we understand these concepts, they're just not communicated as ways to make a living.

This is this weird thing in America, where the authors and drivers of culture are not represented behind the concept, or the camera, or the script, as much as they need to be, in a way that respects the level of creativity that they bring to what it ends up becoming American culture—not Black culture, American culture.

Davis has always had a strong connection to fashion, style and personal expression. Photos: Alberto Vargas

Microsoft embedded themselves in our program for about two days to conduct a series of interviews, to ask diverse students questions as to whether their tool itself is what is making the industry less diverse. And so the fact that they were willing to ask that question: Are we a cause of it? Are there things we can do with our tool to make it more accessible to you? I wholeheartedly respect them for conducting the two full days of, let us learn, let's ask some questions, let us fly out from Washington to do that.

Google partnered with us and another school on the West Coast, took six to eight students, matched them up with a Googler on both coasts, and sort of checked in with them every week, to expose them to the same design problems that you would see on a Google job interview. And so to have them reach into the pipeline, and make sure that they were leveling the playing field by exposing them to Google’s equity engineering team—I mean, just a wonderful name... Those sorts of experiences culminated in a two day design sprint, in both locations. So we have two companies that decided to learn and being able to answer the question, are we relevant? And then do something about it? Yeah, I think if we can comprehensively move forward like that we can tip the scales. That's not just the talk that happens.

Recent work by Davis